Why Teachers Need To Do More Than Have Kids ‘Turn And Talk’

Walk into almost any elementary classroom and you’ll see the teacher introduce a question and then immediately direct kids to “turn and talk” with a partner. I’ve seen this happen as often as every five or ten minutes. And I’ve seen kids have some lively discussions. But here’s what else I’ve seen:

· Kids having a lively discussion about a topic that has nothing to do with what they’re supposed to be talking about

· Kids having a discussion about the intended topic but saying things that don’t make a lot of sense

· One kid holding forth while a partner just listens—or stares into space

· Both kids staring into space, waiting for the teacher to say that time is up

To be sure, there’s truth to the idea that interaction has educational benefits. Learning  doesn’t happen unless students are engaged, and group and pair work can be very engaging for students. But it’s possible to have engagement without learning. And according to one recent analysis, described by Jill Barshay in the Hechinger Report, that may be what often happens.

doesn’t happen unless students are engaged, and group and pair work can be very engaging for students. But it’s possible to have engagement without learning. And according to one recent analysis, described by Jill Barshay in the Hechinger Report, that may be what often happens.

Researchers looked at 71 studies on peer interaction in the United States and Great Britain, where there’s similar pressure to use group and pair work. The studies show that students can learn more from interacting with peers than from working independently, but just telling them to “turn and talk” isn’t enough. Teachers need to give kids guidelines that require them to debate and negotiate, researchers concluded—for example, “Make sure you understand your partner’s perspective.”

That could work—but only if students start out with some understanding of what they’re discussing. Often, they’re directed to “turn and talk” about a topic the teacher hasn’t explained, on the theory that it’s better for them to figure out the facts for themselves. But if learners don’t know much about a topic, they may not yet have a “perspective.” They may not have much to say at all—or they may come to erroneous conclusions. As British educator Tom Bennett has observed, peer interaction may be great for getting students to share opinions or for reinforcing learning through discussion, but “when it comes to factual conveyance, that’s what a subject expert is for.”

Others have pointed to the lack of evidence that simply putting students in  groups or pairs boosts learning—for at least 30 years now. Writing five years ago in a magazine that circulated to the one million members of the American Federation of Teachers, Bennett called group work “one of the most enduring myths I’ve encountered in education.” He investigated “a growing swell of research” that seemed to support its use and concluded it was unreliable. One study, for example, concluded that training students to work in groups made them better at group work but didn’t ask whether it enhanced learning. And yet the myth continues to endure.

groups or pairs boosts learning—for at least 30 years now. Writing five years ago in a magazine that circulated to the one million members of the American Federation of Teachers, Bennett called group work “one of the most enduring myths I’ve encountered in education.” He investigated “a growing swell of research” that seemed to support its use and concluded it was unreliable. One study, for example, concluded that training students to work in groups made them better at group work but didn’t ask whether it enhanced learning. And yet the myth continues to endure.

Then there’s the problem of “social loafing,” which arises when one or more members of a group sit back and let more conscientious or capable members do all the work. Group work—as opposed to briefly turning and talking in pairs—is more likely to occur at upper grade levels and involve projects. One journalist who asked adolescents what they dislike about school found that “most students hate [group projects] and wonder why schools revere them.” Social loafing is apparently rampant. Instead of fostering collaborative skills as intended, group work can give rise to hostility and resentment. One student introduced the journalist to a social media meme: “When I die I want my group project members to lower me into my grave so they can let me down one last time.”

That’s not to say students should never be asked to work in pairs or groups. In addition to supplementing or reinforcing instruction, pair work can be tremendously helpful when students are learning a language. It’s hard to give all  students practice speaking in a large class, and they’re likely to feel less inhibited about making mistakes when they have an audience of one. There’s also evidence that group work can be valuable when a task is complex and a teacher assigns students responsibility for different aspects of it.

students practice speaking in a large class, and they’re likely to feel less inhibited about making mistakes when they have an audience of one. There’s also evidence that group work can be valuable when a task is complex and a teacher assigns students responsibility for different aspects of it.

Still, teachers can read aloud or explain a concept to the entire class and pause periodically to ask questions designed to check comprehension, focus attention on what’s important, and prompt analysis. A whole-class discussion can’t involve every student, but the teacher can expand the possibilities—and keep students on their toes—by calling on kids who haven’t necessarily raised their hands. Further questioning can encourage students to respond to others’ ideas and get a true conversation going. Once students seem to have a basic grasp of the subject matter and possible interpretations, a turn-and-talk activity might be appropriate.

One other potentially powerful and underused interactive technique that reaches all students is writing. That may not look like it involves interaction, but writers are inevitably trying to communicate with a reader, albeit often an unknown one. Writing requires much of the same cognitive work that underlies what scientists call the protégé effect—the boost to comprehension and retention of information that occurs when one person explains something to another. The caveat is that writing is far more difficult than speaking or even reading. Inexperienced writers, a category that includes many teenagers, need to be guided through carefully crafted activities that free up enough cognitive capacity to allow them to grapple with the material they’re writing about.

That’s challenging but far from impossible. Instead of repeatedly having students turn and talk—and running the risk that the talk will lead nowhere or not even happen—teachers could sometimes ask them to take a few minutes to reflect and write.

Broken Education System—and How to Fix It

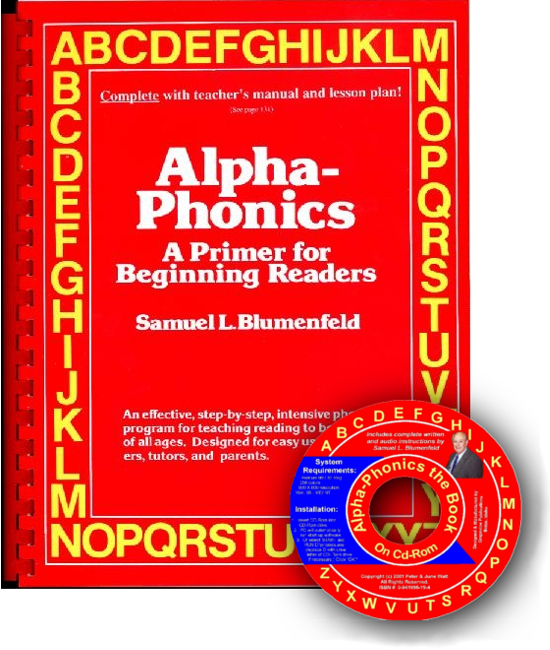

Broken Education System—and How to Fix It Alpha-Phonics

Alpha-Phonics The Alphabet Song!

The Alphabet Song! Water on the Floor

Water on the Floor Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom

Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test

Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test How To Tutor

How To Tutor How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook

How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook