“Unfortunately, I not only know about the reading problem in our schools, but I am well aware of how it feels to be labeled a reading failure. Feeling is a lot more acute than just knowing.”

Mary didn’t start out as a reading failure. She attended kindergarten at a time and place where, “Reading was not allowed.” Undaunted, she joined the childhood social milieu and anxiously awaited first grade, imagining the great fun that lay ahead. Why? Because she would finally learn to read of course!

Mary didn’t start out as a reading failure. She attended kindergarten at a time and place where, “Reading was not allowed.” Undaunted, she joined the childhood social milieu and anxiously awaited first grade, imagining the great fun that lay ahead. Why? Because she would finally learn to read of course!

Sadly, first grade was quite different than she had anticipated.

“All too soon the reality was that reading was nothing more than a guessing game. The teacher would show me a picture of a dog and then the word dog. The next day when the teacher asked me to read, I would read dog for the word did.”

Her teacher would stop her, in the audience of her peers, and tell her that she had missed a word. Similar forms of humiliation continued throughout her first-grade year. Still, she had a great desire to learn to read. When she got home from school, she would try to read her own books, but her enthusiasm was dashed by inability.

Her grandmother would tell her to, “just sound out the words,” but she couldn’t comprehend what she was being told to do. She was clueless. All she had been taught was to look at a picture and try to remember which word matched it. She would try to use her memory to identify the word, which was just a group of nonsensical letters in a block unit. She had not been taught that the letters represented sounds. If she had been, her grandmother’s advice might have been helpful.

Her grandmother would tell her to, “just sound out the words,” but she couldn’t comprehend what she was being told to do. She was clueless. All she had been taught was to look at a picture and try to remember which word matched it. She would try to use her memory to identify the word, which was just a group of nonsensical letters in a block unit. She had not been taught that the letters represented sounds. If she had been, her grandmother’s advice might have been helpful.

Children like Mary are not only hurt by the embarrassment of illiteracy, but they are quite aware of their disappointment to loved ones. There is no doubt that Mary greatly desired to please her grandmother, but she had never been given the means to do so, and this story, unfortunately, is repeated endlessly, throughout many American schools, throughout decades. How many intelligent and enthusiastic people have been destroyed by such unnecessary nonsense? The numbers can’t even be fathomed.

This horrendous wave of intimidation and disappointment could have been prevented so easily, so many times. And it would have been quite simple if only these children had been taught, from the beginning, about the ABC’s and how they worked. Letters stand for sounds. Blending sounds makes words. Words make sentences. Sentences make paragraphs. Paragraphs make books. Children who know how to sound out words are soon reading books. Problem solved.

But without phonics instruction letters have no meaning. Students become confused and anxious. Some escape humiliation by using disruptive behaviors in the classroom. Some become sullen and lose all interest in school. Some learn to “fake it”, with clever ruses. Many of these accounts are beyond shocking. Some compensate by becoming sports heroes, others class clowns. Some drop out of school and pursue lives of crime. Many end up in prison. Fortunately for Mary, her grandmother finally recognized the problem and came to her rescue.

But without phonics instruction letters have no meaning. Students become confused and anxious. Some escape humiliation by using disruptive behaviors in the classroom. Some become sullen and lose all interest in school. Some learn to “fake it”, with clever ruses. Many of these accounts are beyond shocking. Some compensate by becoming sports heroes, others class clowns. Some drop out of school and pursue lives of crime. Many end up in prison. Fortunately for Mary, her grandmother finally recognized the problem and came to her rescue.

“Several years later (even though my family was afraid to help me) my grandmother decided that enough guessing and stumbling over words was enough.”

Evenings after school were spent in more lessons. The difference? These lessons were fruitful. Her grandmother simply taught her the sounds which corresponded to those previously random, letters without purpose. She was amazed!

“I will never forget how she could sound out a word she had never seen before. Once she pronounced it, she would say, “Oh, I have heard of that word,” and then tell me what it meant.

“The nightmare was over. I understood the mystery of words, and reading was easy.”

With the help of a loving grandmother, Mary had conquered illiteracy in her own life. And when she graduated from high school, her eyes were on a single goal. She wanted to rescue other children in the way her grandmother had rescued her. She wanted to teach, with the confidence that every child would learn easily and quickly.

Rudolf & the Rochester Reading Rescuer

“Why should children receive one reading program in the classroom, and then have to go out of the classroom to receive remedial instruction in phonics? Why not teach reading so that children learn successfully the first time they are taught?” Mary L. Burkhardt

Mary’s story is found in the foreword of the book, “Why Johnny Still Can’t Read: A new look at the scandal of our schools (Rudolf Flesch, 1981)”.

This was the second time that Flesch had addressed the same issue in a book. The first time was in 1955 (Why Johnny Can’t Read: and what you can do about it). His message hadn’t changed. Johnny was still illiterate. The notorious they still weren’t listening. Johnny couldn’t read because he hadn’t been taught phonics. He didn’t know how the alphabet works. Mary L. Burkhardt continues in the foreword to this book, to tell how she worked in her own little corner of the world to teach in a way that she believed all children should be taught.

She wound up in Rochester, New York, working for the city school district. This previously timid, struggling child, who had overcome her own trial with illiteracy, came into the teaching field with a vengeance. She came with a battery of well-founded opinions. She believed things like:

“Whether children are ‘advantaged” or “disadvantaged’ black or white, rich, or poor, doesn’t have anything to do with how successfully children learn to read. Such [suggestions] are only excuses for not teaching children to read.”

And:

“Reading is not a mysterious act. When taught logically and systematically, reading becomes a natural accomplishment for the child.”

And:

“If we could only recognize and appreciate the very logical auditory and visual process the child goes through when learning to read, we could save ourselves from all the reading ‘fads,’ ‘bandwagons,’ and ‘shortcuts’ that add to the great confusion about how children learn to read.”

And especially:

“When children are taught to read in a structured, teacher-directed instructional program, they read. When this is not done, many children experience difficulty, and they are then mislabeled as dyslexic, an excuse.”

After nearly a decade of teaching throughout the Rochester Schools, observing reading instruction and results, and guiding other educators, she was honored with the position of Director of Reading. With the help of the Rochester Board of Education and a committee of 40 members, including parents, community group representatives, teachers, and administrators, she was ready to conquer that fearful phenomenon of illiteracy. She organized her resources and guided the selection of curriculum. It was not long before the results came in.

Before the Board of Education Stepped Up

“First, I would like to share with you a few personal experiences and the hope that your children never have to suffer as I did in school.”

This action of the Board of Education didn’t come until Mary had already spent several years assessing the problem. During those years she observed and remembered what she had seen. Her autobiographical account describes a growing concern for the livelihood of her students.

Mrs. Burkhardt’s first year teaching: High School — “Many of my students had previously been told that maybe reading just wasn’t their thing, that they should just keep working and try not to worry about their reading problems.”

Mrs. Burkhardt’s first year teaching: High School — “Many of my students had previously been told that maybe reading just wasn’t their thing, that they should just keep working and try not to worry about their reading problems.”

Mrs. Burkhardt tested students to determine their weaknesses. She learned that most of them had a decoding problem (couldn’t sound out words).

“They were expending a great deal of time and energy guessing at words rather than being able to sound them out.”

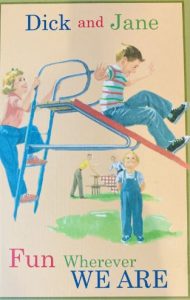

This was the same problem she had described from her own childhood. She had discovered early that “reading was little more than a guessing game.” This problem continues to hound today’s illiterate students. Its source has often been traced to a methodology called look-say, whole word or whole language. Students trained in these programs, or eclectic programs centered around them, are often taught to guess. Much of the curriculum encourages this guesswork, with the use of pictures.

For example, in the story about a circus there may be a large and colorful, drawing of a clown. Within the text is the word clown. The child sees that the word begins with “c”. His eyes roam to the clown, and he tries the word. Since clown starts with the “/c/ as in candy” sound, he guesses, “clown”. He is instantly rewarded. Applause! Take a bow! But he has not read the word.

Some students are better guessers than others. Some students are confused by a process which doesn’t feel like reading — and it doesn’t work for them when they are alone.

Guessing (rather than reading) steals precious time. Clocks tick away, and hour hands travel around their faces, while children play on. These once ambitious students begin to wonder if they are just stupid. Some accept the label. They stress over the disappointment of loved ones, and teachers. Some don’t survive. Others develop compensation skills. They make up for failure with cleverness. They develop tricks, they become sleight of hand artists.

Guessing (rather than reading) steals precious time. Clocks tick away, and hour hands travel around their faces, while children play on. These once ambitious students begin to wonder if they are just stupid. Some accept the label. They stress over the disappointment of loved ones, and teachers. Some don’t survive. Others develop compensation skills. They make up for failure with cleverness. They develop tricks, they become sleight of hand artists.

Many adult dyslexics describe their antics. They tell about privately avoiding reading, so no one will know that they can’t. They choose jobs that won’t uncover their illiteracy. They become great speakers, crowd pleasers, and charismatics. These students in Mrs. Burkhardt’s first year of teaching were no different than many struggling students of today. Presumptions about their (non-existent) inability are now couched in terms like, learning disorder and dyslexia.

Mrs. Burkhardt the Elementary School Teacher — After teaching highschoolers for a couple years, Mrs. Burkhardt moved to the elementary school to try and remediate students who were falling behind in the reading race. She complains that even sixth graders were still guessing words.

“My students were alert and anxious to learn, and the teaching staff was extremely dedicated and worked long, hard hours. At that time, only look-say and eclectic programs were used in the school… In spite of the teachers’ hard work and the children’ readiness and willingness to learn, children were having trouble learning to read. In fact, remedial readers were being generated in my school faster than I could remediate them.”

Mrs. Burkhardt tells of a student she has never forgotten, an eager and always smiling, remedial fifth grader. He and his classmates still struggled with decoding, so she spent part of each class working on just that – sounding out words. As they were reading, one of the classmates decoded, astronaut. This happy boy shouted out with joy, “So that’s what the word astronaut looks like!”

Mrs. Burkhardt suggests that astronaut had probably been in this boy’s listening and speaking vocabulary for a long time, maybe even before he started school. This was the key to an encouraging realization.

“As soon as they are able to sound out words, they can enter them into their reading and spelling vocabulary. Once they can decode a word, they then may automatically know the meaning. If the word read is totally new to the child, he can then immediately be taught its meaning.”

Mrs. Burkhardt – Supervisor — From there Mrs. Burkhardt climbed to a position as the Supervisor for Elementary and Secondary Reading Programs.

Mrs. Burkhardt – Supervisor — From there Mrs. Burkhardt climbed to a position as the Supervisor for Elementary and Secondary Reading Programs.

“[We] worked to remediate students as rapidly and successfully as possible… Students daily received an extra “shot” of reading instruction. The reading teachers worked to teach them the phonics and comprehension skills they needed. Each student was tested throughout the entire school year. The teacher was teaching-testing: teaching-testing: and individualizing instruction to meet each student’s reading needs. After three years, the proof was again evident. Students who were thought of as having limited reading capabilities made significant progress every year.”

This supervisory experience, encouragement from her success in that position, a compassionate empathy for struggling readers, and a continually growing, zealous flame, made Mary Burkhardt the perfect candidate for her appointment as Director of Reading. When she embarked on this next adventure, the average first graders in her district were already three months below grade level at the end of their school year, and the average sixth graders were two years behind. She soon demonstrated that this need not be the case.

Five Years Later — By implementing phonics-first programs, Mary Burkhardt proved what she had insisted all along. Once students could successfully sound out words, they were safely on the road to reading. Many new first graders were decoding words in text within 3 to 4 months (because they had learned how the alphabet works). They returned from Christmas break ready to read real books!

One school librarian reported to her that second graders were coming into the library and asking for chapter books, and that they were reading “like the fifth graders used to read”. Average first graders were now above grade level at the end of their first year, and second through sixth graders finished out their schoolyears at grade level.

“Today students automatically decode [sound out words] logically, systematically, and successfully. This enables them to use their energy to read for meaning and understanding, which of course is the ultimate purpose and joy of reading.”

Mary Burkhardt went on to become a leader in organizational management for companies around the world. Her linked-in profile describes her as an “experienced global change agent” who has overseen thousands of employees. Plus, she is the CEO of her own company. Obviously, as the Reading Director for the Rochester Schools, she was already a global change agent. What an amazing accomplishment — to change the lives of young people, over, and over again, through her gift. She taught them to read for real!

by Meg Rayborn Dawson

by Meg Rayborn Dawson

MS, Exceptional Student Education (Univ. of W. Florida) emphasis on Applied Behavior Analysis

MA, psychology (Grand Canyon University)

Bachelor of Arts (Northwest Nazarene Univ.)

**********************************************************

Be a HERO: Teach a Child to READ

Did you know every year many 1,000’s of parents teach their own children to READ? Many of them have used Alpha-Phonics because they have found it can easily be used to teach their children to read. Your Kids can make a lot of headway in only a couple of weeks with this proven program. Alpha-Phonics is easy to teach, is always effective and requires no special training for the Parent. It works ! And it is very inexpensive. You CAN DO it !! Follow the links below to know all about the time-tested (38 + years) Alpha-Phonics program:

Alpha-Phonics

Alpha-Phonics The Alphabet Song!

The Alphabet Song! Water on the Floor

Water on the Floor Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom

Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test

Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test How To Tutor

How To Tutor How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook

How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook