Why is Phonics called Phonics &

What does this Have to do with Reading Instruction

“The Phoenicians wrote from right to left

as do those who write Hebrew today. But eventually

the Greeks settled on a left-to-right direction.”

Samuel L. Blumenfeld*

It is not difficult to guess that the word phonics is connected to the Phoenicians, but what is the significance of this and how does it apply to reading instruction?

It is not difficult to guess that the word phonics is connected to the Phoenicians, but what is the significance of this and how does it apply to reading instruction?

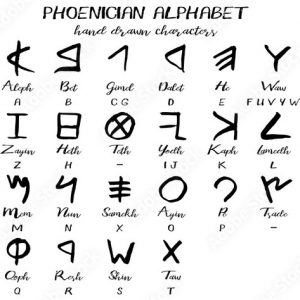

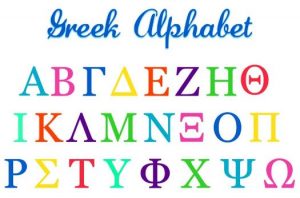

The alphabet, it appears, was invented by the Phoenicians some three thousand years ago. The Phoenicians, who lived in the area we now call Lebanon, spoke a Semitic language and were neighbors of the Greeks with whom they traded. The Phoenicians used their writing system to help record many of their commercial transactions. The Greeks were intrigued by the facility acquired by the use of a sound-symbol system, and they tried to use it for their own language.  But Greek was quite different from Phoenician in its sounds, and it took a great deal of experimentation before the Greeks devised a complete set of symbols or letters with which they could represent every sound of their language.

But Greek was quite different from Phoenician in its sounds, and it took a great deal of experimentation before the Greeks devised a complete set of symbols or letters with which they could represent every sound of their language.

To facilitate the learning of the alphabet, each letter was given a distinct name, borrowed from the Phoenicians in most cases, in which the sound of the letter was given. Thus, we got alpha, beta, gamma, etc. The important point to note here is that the name of the letter was quite distinct from the letter’s sound value, and there was no confusion in the minds of the Greeks about the two.

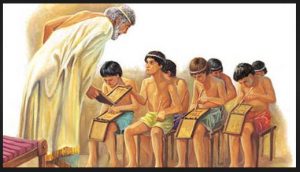

In those days there was no such thing as a dictionary or spelling guide. This was long before printing. If you knew the alphabet and wished to use it, you simply sounded out each word you wanted to write and then set down the letters representing the sounds in the same sequence as the sounds themselves were uttered. This seems like so obvious a procedure, yet two thousand years later we shall find professors of education doubting its simple validity. At first, you used the alphabet in any direction you wanted. The Phoenicians wrote from right to left as do those who write Hebrew today. But eventually the Greeks settled on a left-to-right direction.

In those days there was no such thing as a dictionary or spelling guide. This was long before printing. If you knew the alphabet and wished to use it, you simply sounded out each word you wanted to write and then set down the letters representing the sounds in the same sequence as the sounds themselves were uttered. This seems like so obvious a procedure, yet two thousand years later we shall find professors of education doubting its simple validity. At first, you used the alphabet in any direction you wanted. The Phoenicians wrote from right to left as do those who write Hebrew today. But eventually the Greeks settled on a left-to-right direction.

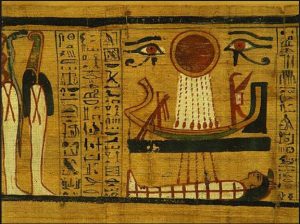

Before the invention of the alphabet, writing was ideographic. Language was represented by picture-symbols which required a great deal of memorization and was never very accurate. It was easy enough to represent commonplace objects and simple actions by picture symbols. But when it came to communicating complex philosophical abstractions or great subtleties, ideographs were inadequate. The alphabet was a tremendous improvement. Once you mastered the sound-symbol system, you could write down any thought in precisely the manner you wanted it to be conveyed. This enabled the Greeks to expand the mind’s capacity to think and work, and it permitted a tremendous advance in man’s intellectual development.

Before the invention of the alphabet, writing was ideographic. Language was represented by picture-symbols which required a great deal of memorization and was never very accurate. It was easy enough to represent commonplace objects and simple actions by picture symbols. But when it came to communicating complex philosophical abstractions or great subtleties, ideographs were inadequate. The alphabet was a tremendous improvement. Once you mastered the sound-symbol system, you could write down any thought in precisely the manner you wanted it to be conveyed. This enabled the Greeks to expand the mind’s capacity to think and work, and it permitted a tremendous advance in man’s intellectual development.

According to Dr. Mitford M. Mathews*:

“Other peoples, such as the Babylonians and the Egyptians, had caught glimpses of the desirability of having signs represent sounds, not things, but they were never able to break with convention to the extent of setting aside picture writing in favor of letter writing. The fundamental defect of picture writing was that it was not based upon sounds at all. Greeks saw this basic weakness and by avoiding it achieved everlasting distinction.”

How were the Greeks able to “break with convention”?

Dr. Mathews continues:

“The secret of their phenomenal advance was in the vividness of their conception of the nature of a word. They reasoned that words were sounds, or combinations of  ascertainable sounds, and they held inexorably to the basic proposition that writing, properly executed, was a guide to sound.”

ascertainable sounds, and they held inexorably to the basic proposition that writing, properly executed, was a guide to sound.”

Perhaps this is one reason why the Greeks produced such great dramatists: their infatuation with and love of the spoken word, and their determination to capture it as accurately as possible for themselves and future generations. It is worth noting that much of the ancient Greek literature we enjoy today was written in the form of dialogues.

*Samuel Blumenfeld, author of Alpha-Phonics: A Primer for Beginning Readers gives this short but concise account of the history of the alphabet, gleaned from the work of Dr. Mitford M. Mathews, author of A Dictionary of Americanisms on Historical Principles (1951) and editorial consultant for the Webster’s New World Dictionary from 1957 to 1981:

Coming Next:

How the Alphabet Began Part 2:

How Greek Children Learned to Use the Alphabet

by Meg Rayborn Dawson (homeschooling mom of 9)

author of: Dyslexic No More: Saved by the ABC’s

MS: Exceptional Student Education (Univ. of W. Florida) emphasis on Applied Behavior Analysis

MS: Exceptional Student Education (Univ. of W. Florida) emphasis on Applied Behavior Analysis

MA: psychology (Grand Canyon University)

BA: (Northwest Nazarene University)

***********************************************************************************

“I used Alpha-phonics to teach all 6 of my daughters to read as well as tutoring other children. Now my oldest daughter wants to use Alphaphonics to teach her own son to read using Alphaphonics!! I would like to purchase a copy and CD for her.”

Marie Gossling, November, 2015

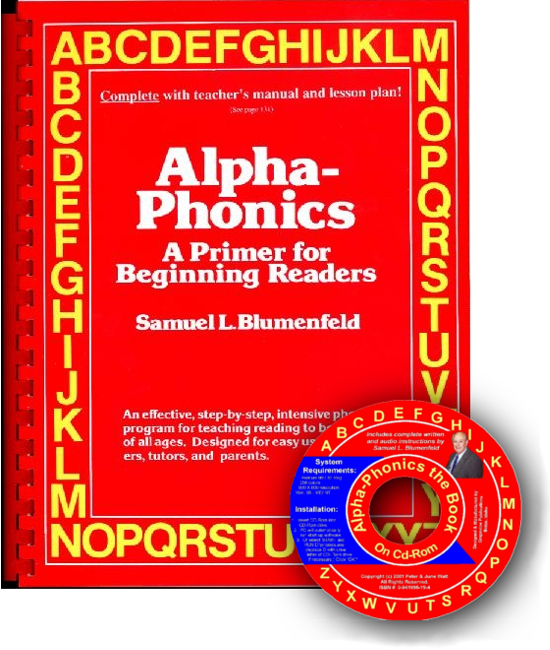

HOW TO ORDER the 2022 Edition of Alpha-Phonics

Alpha-Phonics

Alpha-Phonics The Alphabet Song!

The Alphabet Song! Water on the Floor

Water on the Floor Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom

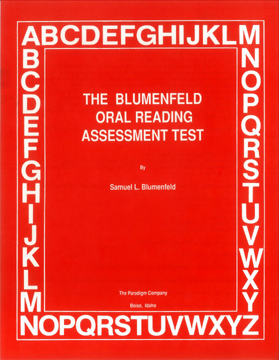

Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test

Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test How To Tutor

How To Tutor How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook

How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook